There is a basic question that must be addressed when pondering the nature of consciousness, and that is: why have consciousness at all? The brain processes a great deal of information below the level of conscious awareness, from visual to auditory to tactile, and then the integration of all of these before they can be brought into conscious awareness. Yet conscious awareness itself seems much more limited in the amount of information that it can handle at a time—5 to 9 “chunks” of information, at a time, it would seem. So why rely on conscious awareness as heavily as we do? It certainly seems, at least from this angle, much less able than non-conscious processing—yet, given its apparent efficacy in raising humanity to the heights of culture and insight that we enjoy today, it surely has something essential to offer us.

The prefrontal cortex is the latest structure to appear in the evolution of the brain, and is the structure that shows the greatest development between humans and our closest biological relatives. Furthermore, it is known to mediate a great deal of the abilities considered distinctly human, such as planning, reflection, and empathy, all of which apparently require conscious awareness. Surprisingly, however, a vast abundance of the projections that the prefrontal cortex sends back to more primitive, sub-cortical structures are inhibitory—they function largely to suppress activity in these regions. In fact, this has led several researchers to rethink the concept of free will and, somewhat amusingly, refer to it rather as “free won’t,” in that we are mainly choosing what not to do, of all of the responses recommended by sub-cortical structures. And this is where we might find a reason for conscious awareness.

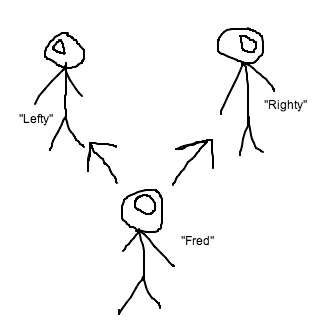

Consciousness relies on a crucial ingredient for dealing with the world in the way that the prefrontal cortex specializes in doing: it removes behavior from the moment-to-moment sensory perceptions incessantly presenting themselves to sub-cortical brain regions. Instead of constantly responding to each and every stimulus as it comes in, consciousness introduces a disconnect that allows reality apart from oneself to be treated as perceived, and thus distinct from the self and manipulable. Non-conscious responses don’t require perception in the same way that conscious processes do. In order to consciously ponder a course of action while planning, you need a virtual representation to work with, and in order to do that, you need some distance between yourself and the object being represented. Every day perceptions such as the visual field in front of you may function in a very similar manner: a stimulus presents itself, is processed by sub-cortical structures, and then a course of action is offered up to conscious awareness to be chosen or discarded by conscious reflection. There is a whiff of “opponent processing” going on in this narrative, something that comes up a lot in systems biology: two structures working in opposite directions in order to better center around a single desired outcome. Non-conscious, sub-cortical processing is largely reactive, leading to sometimes extreme, reflexive responses; conscious prefrontal processing, on the other hand, divorced from the constant demands of the environment, is more receptive to multiple courses of action, but can sometimes leave us unable to settle on an alternative. With the two of these working with opposing aims, however, behavior that is reactive enough to survive, but receptive enough to be a functioning member of society, can be attained.

This is far from a coherent theory or hypothesis, but the parallels between the roles of sub-cortical and non-conscious processes on the one hand, and prefrontal and conscious processes on the other, along with the connections between the two, are surely going to be important in mapping human consciousness.